Neurodiversity Parenting Plans

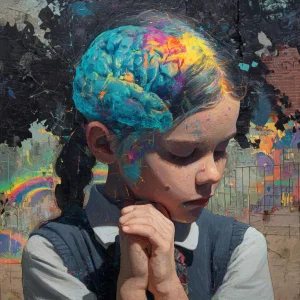

Parenting any child across two households is a balancing act, but when a child is neurodivergent (meaning their brain develops or processes information in a different way), such as in cases of autism, ADHD, dyslexia, or related  profiles, the stakes rise and so does the need for nuance.

profiles, the stakes rise and so does the need for nuance.

Courts, therapists, teachers, and extended families all want to support these children, yet the blueprint for doing so usually starts with the parents and the professionals advising them.

The idea of neurodiversity is relatively new, first articulated in the 1990s as a strengths-based response to medical labels. Earlier generations used the phrase “special needs,” a term that grew out of U.S. disability statutes in the 1960s and 1970s. While “special needs” highlighted the right to individualized instruction and services, advocates note that it also framed children by their challenges, not their capacities. Neurodiversity turns that framing on its head: differences are expected, not exceptions, and effective plans focus less on “fixing” a child and more on tailoring environments so children can flourish.

Unfortunately, the law has not fully caught up with this shift in mindset. Florida’s Parenting Plan statutes lists a number of broad factors such as the parents’ mental health, the child’s school schedule, and community ties. These rules cast a wide net meant to catch every conceivable family situation, yet they are blunt tools for children who react strongly to sensory triggers, require medication at the same time every day, or melt down when routines change without warning. While judges have discretion to account for developmental needs, without concrete data they often revert to default 50/50 rotations that work for many neurotypical siblings, but may destabilize neurodivergent children.

Families can close that gap by grounding their proposals in three realities: routine is regulation; transitions are stressors; and “one size does not fit all.” One technique that I have pulled from years of litigating complex cases involving injuries is to create “Day-in-the-Life” logs or short videos that capture medication rituals, school-morning hurdles, and bedtime decompression. These “Day-in-the-Life” videos can complement testimony and allow judges to see why; a proposed schedule will or will not work for the child.

Consistency also depends on robust, low-conflict communication. Co-parenting apps like OurFamilyWizard let parents post schedules, doctor appointments, and even sensory-diet notes all in one location. I recommend that the Parenting Plan further specify how quickly parents must acknowledge messages and/or how to escalate true emergencies. The additional structure places the burden of clarity on the adults, sparing the child from acting as a go-between or “messengers.”

Parenting style matters, too. When creating similar homes, it helps if both households agree on a core set of rules such as bedtimes, screen-time limits, and homework rituals. While the structure is the same, each parent should allow the other parent flexibility in less crucial areas. One thing that is often overlooked is that the Parenting Plan should specify that disciplinary measures remain consistent, so the child never associates structure with one parent and chaos with the other.

Physical environments often need matching structure as well. Weighted blankets, noise-canceling headphones, identical shampoo scents, or color-coded visual schedules can exist in both homes, so the child’s body does not need to recalibrate every exchange night.

Sensory-friendly design costs money and traditional child-support worksheets rarely cover extra supports. Lawyers and parents should consider adding a “neurodiversity fund” line item so that each parent contributes a set percentage of income towards the fund and that requires costs incurred by one parent to be reimbursed within a stated timeline. I have used this in many cases and allowing both parties access to seeing this account increases transparency and trust. In the alternative, you can consider an upward deviation in child support due to extra costs and expenses. See, Florida Statute 61.30 (11)(a).

Decision-making authority is another flashpoint. Florida law allows courts to award joint custody (or the current terminology in Florida is “shared decision-making authority”), sole custody (“sole decision-making authority”), or ultimate decision-making authority, to parents. However, neurodivergent children often have multiple specialists—neurologists, occupational therapists, speech pathologists—all weighing in. While you should never delegate your responsibility as a parent to an expert, it is important to think about and consider what dynamic will allow for the greatest flexibility and consistency given the outside feedback.

Sometimes, we have families where one parent works, and the other is primarily responsible for taking the child to doctor’s appointments. It is important that the working parent is kept up to date with clear expectations on communication and it is also important that the parent taking the child to the appointment can make real time decisions without unnecessary delay. One idea that we have seen work is when a parent gets assigned a particular domain (for instance, shared parenting for most issues, but one parent handles medical decisions). Think about what kind of prior notice-and-consent would be required before making major changes.

If you have a higher conflict coparenting relationship, you may want to consider appointing a neutral professional—a parenting coordinator with neurodiversity training—as a tie-breaker if consensus stalls. Our experience that the courts are cautious when making decisions around medication, therapy, or even diagnosis itself. High conflict coparenting relationships can derail a child’s progress if left to courtroom showdowns.

Because co-parenting disputes flare under stress, an effective plan includes a laddered dispute-resolution path. Start with direct written discussion through the app; if no agreement, exchange formal written proposals; next, consult the designated neutral; then mediate; and finally file a court petition only as a last resort. Embedding this graduated approach into the plan signals to the court that parents intend to exhaust collaborative tools before relitigating, an approach that saves time, money, and emotional bandwidth.

The child’s developmental stage adds yet another layer that is worth considering. Younger children, who form secure attachments through proximity, often do best with short, frequent visits and gradual extended overnights. Elementary-age children thrive when school-night routines stay identical no matter whose roof they are under. Middle-school schedules can incorporate longer weekend blocks while preserving weekday consistency, and teens can voice personal preferences so long as parents remember that court orders and the law—not children—make the ultimate decisions.

Parents with neurodivergent children should look at each transition point as an opportunity to revisit and revise the Parenting Plan. Maintaining this routine keeps updates/revisions proactive rather than reactive.

Professionals serving these families must embrace interdisciplinary collaboration. Lawyers translate clinical recommendations into enforceable clauses; therapists educate judges on symptomology; financial planners forecast long-term costs of care. Judges, for their part, benefit from clear, jargon-free briefings that tie statutory language to concrete needs.

As an example of the interplay between professionals and the Courts, consider this example. Florida Statutes § 61.13 requires courts to examine whether the parent can maintain routine. A parent brings in the Occupational Therapist (“OT”) records which show the child’s self-injurious behavior spikes if he is not in bed by eight, so both households must observe that bedtime. Presenting data this way turns generalized desires into individualized Parenting Plan language that is enforceable and beneficial for the minor child.

Parents, meanwhile, need emotional permission to prioritize mutual goals over positional wins. When both homes replicate routines, when communication runs through structured channels, when disagreement routes through mediation and not text-message battles, then children will internalize stability instead of volatility. Perhaps most importantly when parents model resilience children will become more resilient. Yes, this child’s life is split across households, but if grown-ups can cooperate, ask for expert help, and adjust plans as the child grows then the child will be set up for success.

By layering neurodiversity science onto statutory frameworks, parents and their advisers can weave a plan together that holds children safely without tangling them in fights or forcing square pegs into round routines.

If your family is separating or divorcing, consider gathering multidisciplinary insights early, documenting the child’s real-world day, and insisting on a parenting plan that reads less like generic template and more like the owner’s manual for your one-of-a-kind child. While this may cost you more time and money up front, it will pay off with calmer child exchanges, fewer emergency calls to attorneys, and the priceless assurance that both households feel like a home to your child.

For personalized guidance on crafting or modifying a neurodiversity-informed parenting plan, consider consulting a family-law attorney who regularly works with therapists, educators, and neurodivergent advocates. The attorneys at TK Law are familiar with these issues and they can help you look ahead.

If you have any questions, feel free to call us at 407-834-4847 and let our team of professionals guide you and your family through this undoubtedly difficult time.